In 2014, the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault convened a “data jam”. This was comprised of technologists, policy experts, and survivor advocates who were there to ‘brainstorm new ways to use technology' to develop ‘more effective and transparent responses to incidents’ of sexual assault on campus.

A year later, when a woman in Florida attempted to report her sexual assault, she was told she was making false claims. She said she was asleep at the time of the assault; her FitBit, however, showed that she was awake and moving. She was charged with false reporting, making false alarm, and tampering with evidence.

Besides involving sexual assault, these two events may appear unrelated. However, a closer investigation of the growing market for anti-rape or safety technologies (e.g. wearable alarms, tracking applications, online reporting tools) shows that the data jam’s desire for efficiency and transparency is not so far apart from the Florida law enforcement’s response to the FitBit data in the rape case.

Why has the Task Force turned to technology for ‘more effective and transparent responses’ to sexual assault? What motivated law enforcement to trust FitBit data over the woman’s story? What does it mean to seek out efficiency and transparency through technology and data to address sexual assault?

This article examines how the prevailing cultural notion of sexual assault victims as liars, and the widely held belief of technological objectivity, converge to instruct the design of anti-rape technologies. Design processes reveal how the developers intended these devices to be used, by targeting ideal users, and prompting users to collect certain kinds of information.

These implications are situated in the context of American higher education where anti-rape technologies are increasingly popular and becoming embedded into campus safety infrastructures. Thanks to the activism of student survivors and civil rights advocates in recent years, American higher educational institutions have come under fire for their mishandling of campus sexual violence1. In response to this growing scrutiny, many universities are turning to technological solutions. Over 120 institutions, ranging from large state schools to small liberal arts colleges, have adopted mobile reporting platforms, such as Circle of 6, EmergenSee or LiveSafe. Others, such as the State University of New York System, have opted to create their own reporting tools.

Anti-rape technology devices and their features

“Anti-rape” or “safety technology” loosely describes (mostly) digital tools aimed at preventing or responding to gender-based violence. The following chart draws from an empirical study of anti-rape features by Bivens & Hasinoff (2017) that details their form, examples, and characteristics.

| --- | Prevention-oriented | Response-oriented |

|---|---|---|

| Form | Wearable; web and/or smartphone applications; SMS messages | Web and/or smartphone applications |

| Examples | bSafe: mobile application that can send location and help messages to designated contacts; make fake phone calls; set check-in timers. Circle of 6: smartphone application to send alert messages to, or request help calls from, up to six designated contacts. LiveSafe: mobile safety communication platform that collects crowdsourced intelligence to map suspicious activities; sends in-app reporting/messaging to campus security. SafeTrek: smartphone application with an alarm button that automatically sends location information to local police when safety button is released by the user | Callisto: web-based application with trauma-informed questions for confidential documentation; matching feature identifies other documentation with identical perpetrator(s) and enables Title IX or police reporting. Lighthouse: anonymous and encrypted reporting tool that can escalate reports to campus security/law enforcement; features real-time chat with campus resources. My Plan: smartphone application that provides risk assessment to female-identified victims of partner abuse |

| Features and characteristics | •Automatic reply •Push notifications •May encrypt data •Check-in features (calls, timer, messages, notifications) •Diversion calls/messages •Sends alert to friends, campus safety, hotlines, counselling, and/or police •Real-time chat support with friends, campus safety, hotlines, and/or counselling •Loud alarm •Location features (GPS, geofence) • Database and/or map of on-campus, local, and/or national resources | •Automatic reply •Push notifications •Likely to encrypt data •Non/anonymous in-app reporting with text, photo, audio, or video to friends, campus safety, hotlines, counselling, and/or police •User-inputted details •Quick-exit •Sends alert to friends, campus safety, hotlines, counselling, and/or police •Real-time chat support with friends, campus safety, hotlines, and/or counselling •Location features (GPS, geofence, mapping) •Database and/or map of on-campus, local, and/or national resources •Information on how to support victims |

There is also a great degree of heterogeneity in how these devices are made. A few, such as Callisto and Circle of 6, have been developed by survivors; many have not. Some have a clear focus on sexual violence; others appeal to generic concern for personal safety. Some partner with campuses, workplaces, and the police; others work independently. Some provide customisation; others do not.

Missing Design

Despite the heterogeneity, the growing popularity of these technologies, especially in higher education, has been described as an ‘anti-rape industry’. The reception has been polarising: some celebrate their innovation in placing safety in the users’ hands, while others criticize them for perpetuating the “stranger danger” myth. At the heart of these debates are notions of women’s agency, bodily regulation, and the liberatory potential (or not) of emerging technologies. However, the focus has largely remained on end-users’ behaviour, veering into arguments about whether women should or should not use these apps.

Amidst these moral projections, design has been overlooked. What is telling about the particular ways in which these technologies are designed is that they indicate certain logic of use. From colour scheme to location of menu button, the interface has been carefully laid out to interact with the user in ways that prompt certain behaviours 2.

As information scholar Karen Levy notes, the design of anti-rape technologies exhibits the prevailing cultural attitude that sees rape ‘fundamentally, as a problem of bad data’. Levy writes that smartphone apps that collect ‘crowdsourced intel’, wearables for ‘immediate tips’, and ‘transparent reporting tools’ aim to ‘tell the truth about an encounter, with the objectivity and dispassion of a database.’ For devices that claim to support rape victims, this faith in the objectivity of data-driven technology stands in opposition from the dominant social view that survivors who tell their stories are not to be trusted. If the politics of rape raised the question of who has credibility over whom, the introduction of data-driven technology now asks: what has credibility over whom?

The remaining sections investigate two examples of anti-rape applications to illustrate how these attitudes about sexual violence and technological objectivity are inculcated in their design. The first details how the gendering of personal safety places the responsibility to remain safe on the feminised user. The second explores a reporting tool’s attempt to produce “objective” sexual assault data.

Personal Safety = Women's safety

Prevention-oriented technologies may present safety as a universal concern, but their marketing and design reflect an active gendering process in which safety is feminised as the woman’s responsibility. Consider SafeTrek, a mobile application with an alarm button that automatically connects the user to local police. SafeTrek presents itself as a tool for everyone that ‘allows you to proactively protect yourself without the heavy commitment of calling 911’. Its main interface displays a dark blue background on which a lighter blue button in the shape of a shield instructs, ’HOLD UNTIL SAFE’. With the minimalist aesthetic of the interface and blue colour scheme, the application appears gender-neutral.

(SafeTrek home screen. Screengrab from 2 August 2017)

(SafeTrek home screen. Screengrab from 2 August 2017)

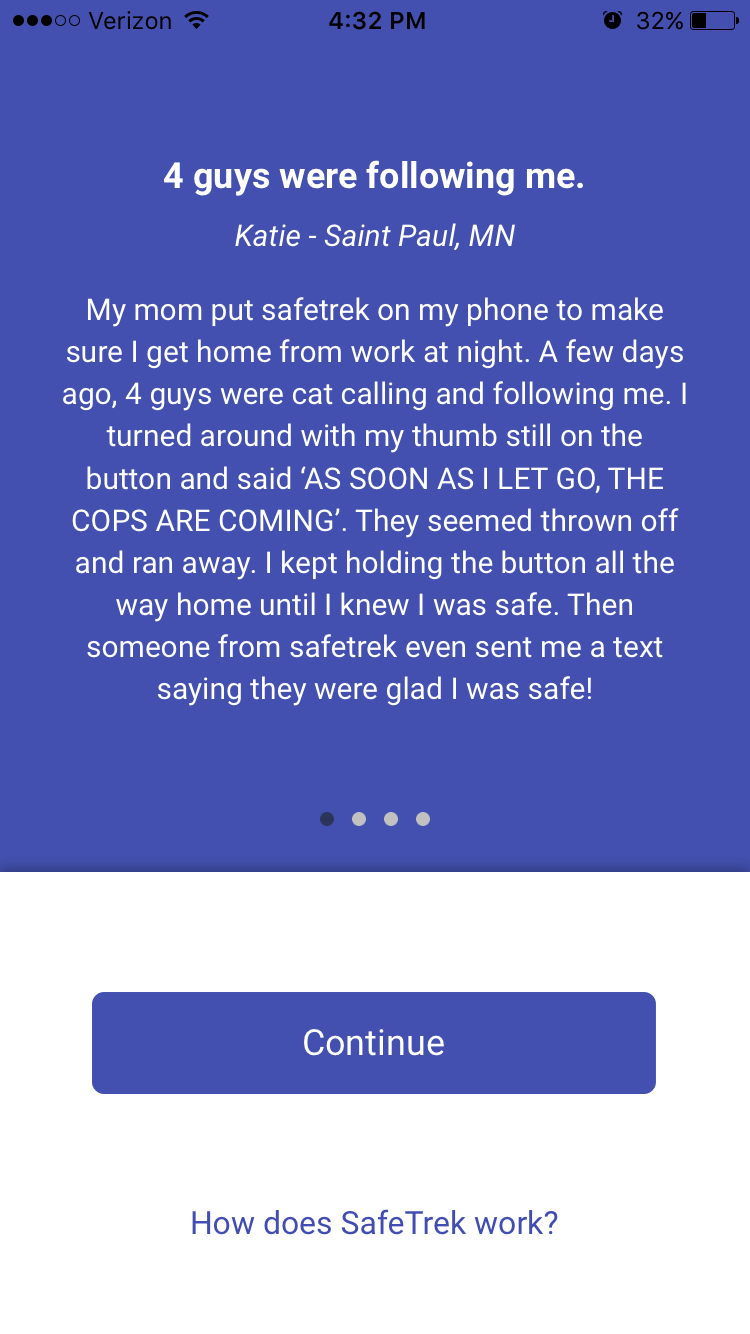

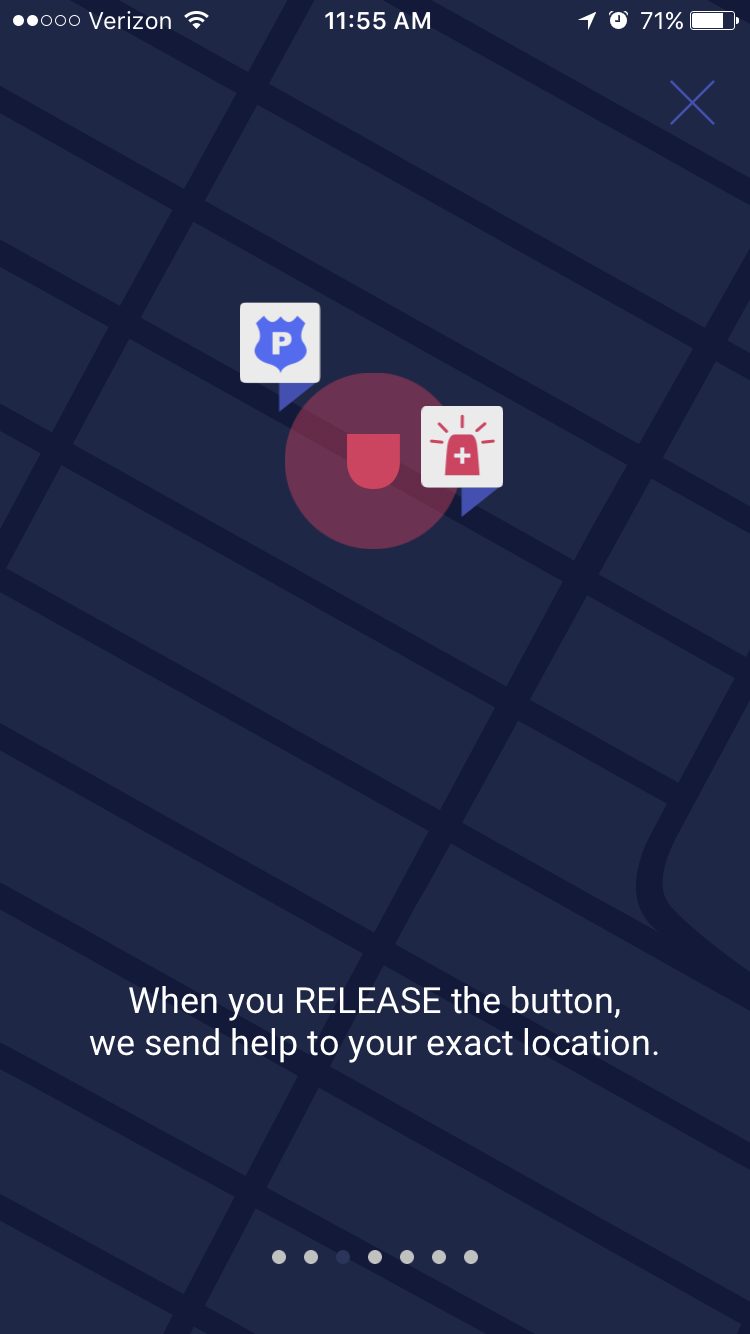

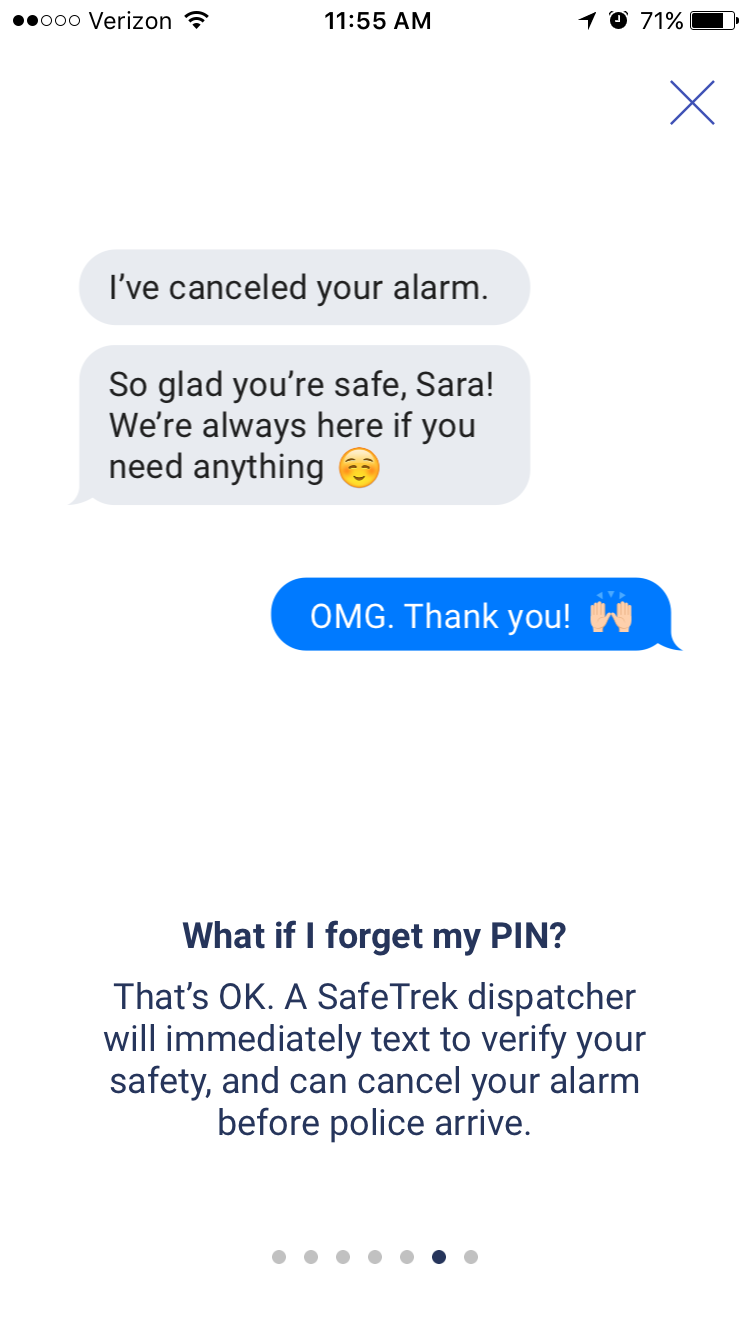

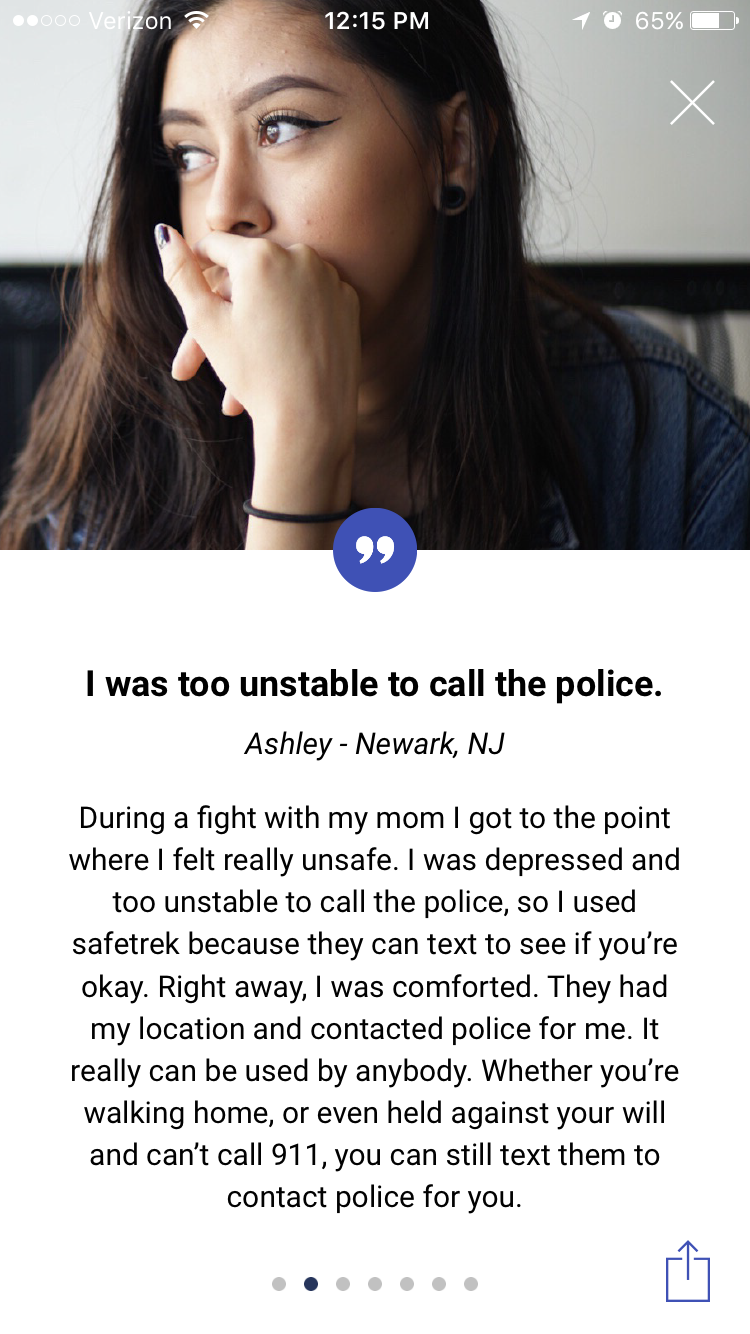

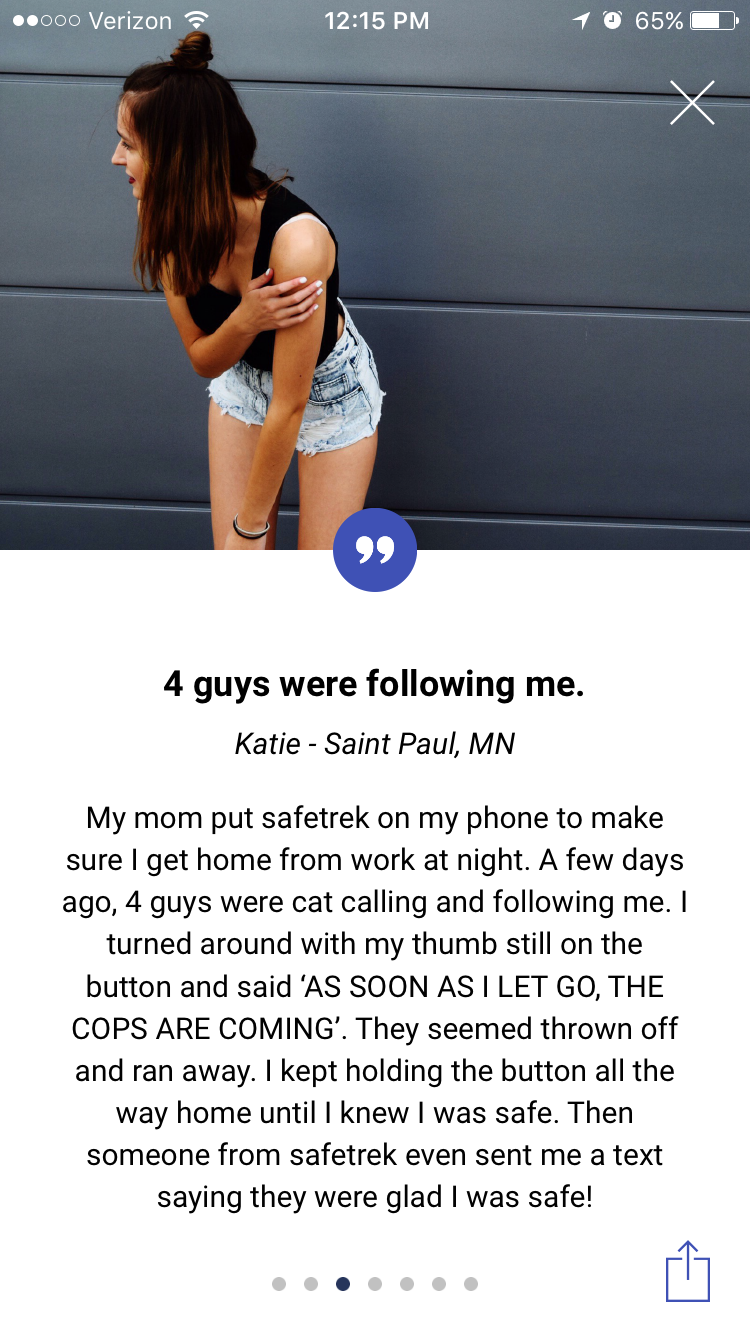

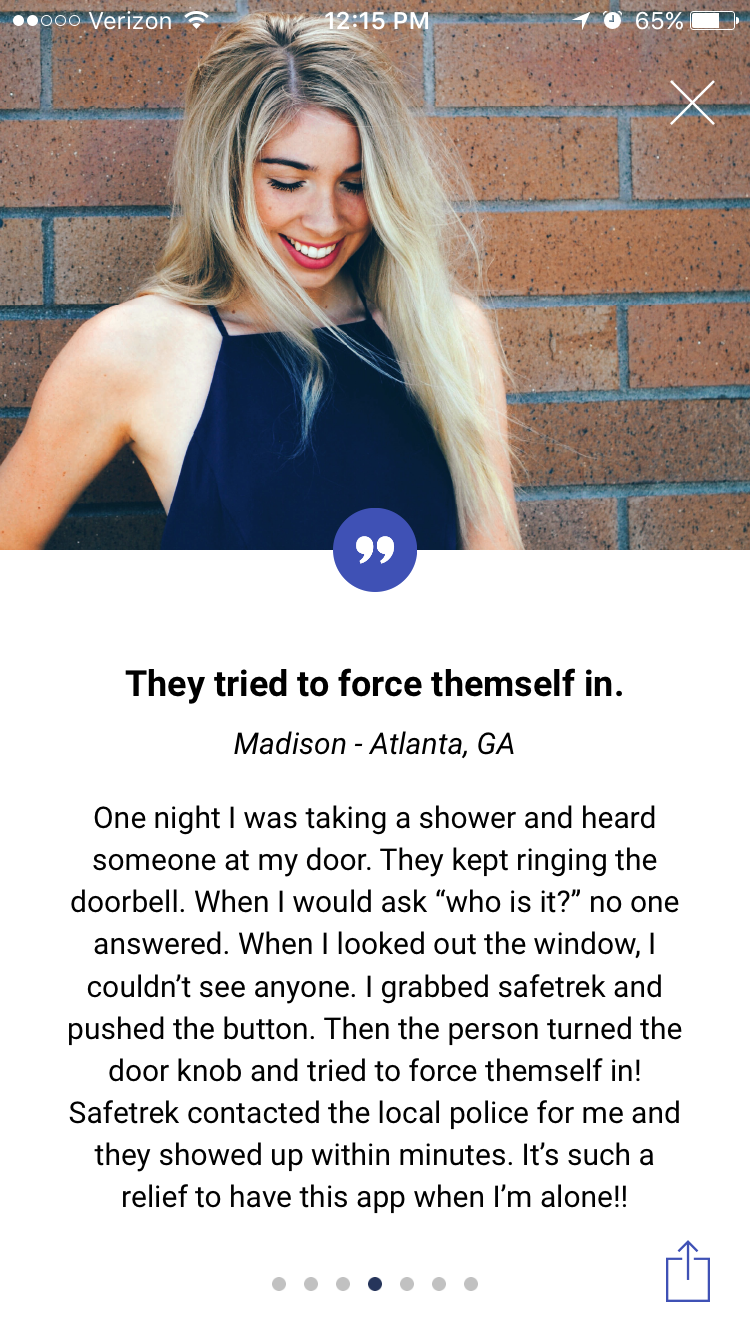

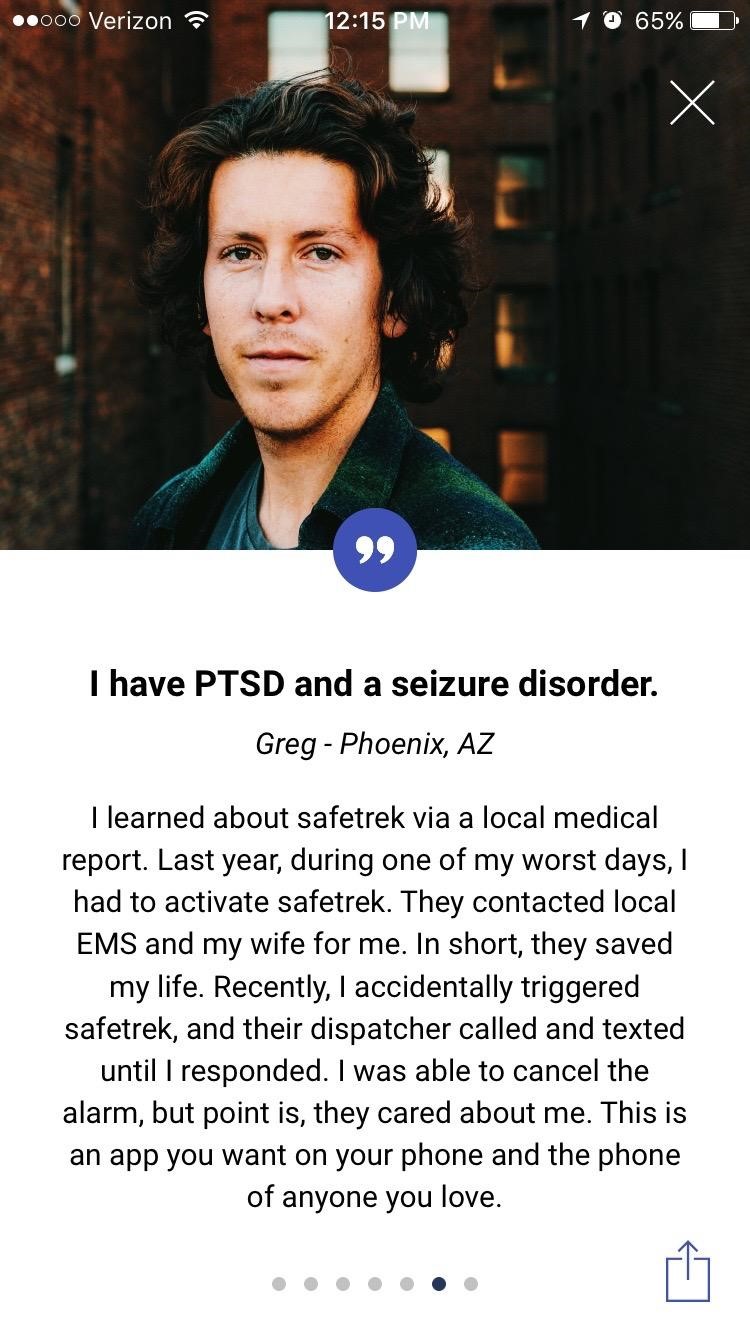

Upon closer examination however, its design and marketing demonstrate how the user and the contexts of use are feminised. When downloading the application, four user testimonials are shown: of the four, three detail contexts of use in which the users are women experiencing threats from unknown men (See the ’4 guys were following me’ screengrab below). A few instruction steps later (’When you RELEASE’ screengrab below), SafeTrek displays a text message exchange about alarm cancellation between an ungendered SafeTrek dispatcher and the user, who is referred to as ‘Sara’ (’I’ve cancelled your’ screengrab below).

(Instructions after downloading. Screengrabs from 1 and 2 August 2017)

(Instructions after downloading. Screengrabs from 1 and 2 August 2017)

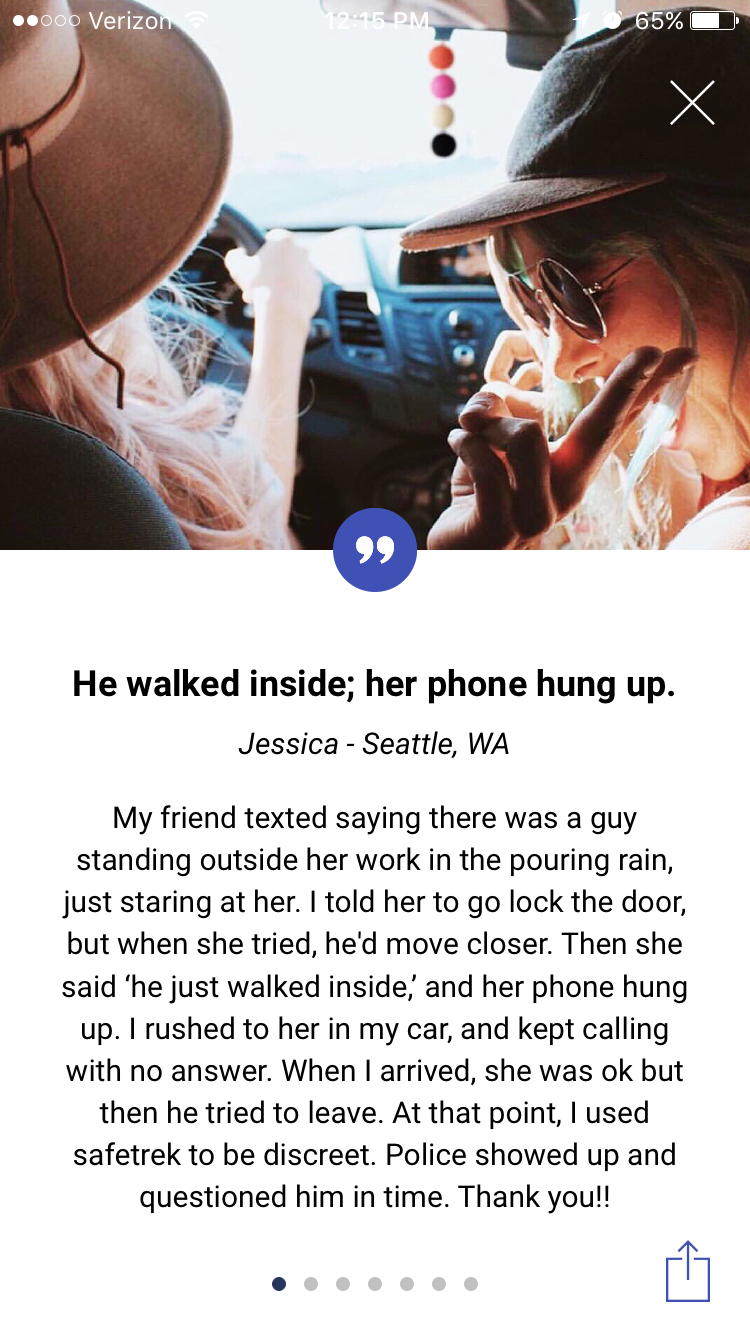

The ideal user is further gendered as a woman in the ’Real SafeTrek Stories’ feature under the drop down menu on the upper left hand corner. Of the six stories featured, five are by users with feminine names. These users show accompanying photographs of (mostly white) women standing, traveling, or engaged in an activity on their own, who presumably submitted the stories themselves. The only image/story of a male user is also the only testimonial involving a non-”stranger danger” narrative. The white femininity of safety presented here not only reifies the notion of white women as more worthy of protection, but also erases the heterogeneity and complexity of sexual violence against those who are of colour, identify as men, trans*, and genderqueer, or those who experience intimate partner abuse.

(’Real SafeTrek Stories’. Screengrabs from 5 August 2017)

(’Real SafeTrek Stories’. Screengrabs from 5 August 2017)

Similar images of the user as a young woman, alone in public, are exhibited in marketing materials. The app’s website homepage displays a slogan: ‘Never ___ alone’, with words like ‘walk’, ‘feel’, ’travel’, and ‘cross campus’ appearing on the blank. The text is overlaid against faded images of women walking alone in deserted places, shot from behind or the side, in some cases showing the woman visibly clutching her purse as she walks alone at night.

SafeTrek homepage. Screengrab taken 5 August 2017

SafeTrek homepage. Screengrab taken 5 August 2017

SafeTrek’s general language of personal safety may posit that anyone can ‘feel scared’ or be ‘in danger’, but the app’s design and how it presents itself visually suggests that the designers have gendered scenarios of use in mind. In rendering personal safety as “women’s safety”, apps like SafeTrek affirm the dominant assumption that the onus of not being assaulted rests on women. Returning to the app’s mission statement, if personal safety is something to be ’proactively protected’ by willing users with a touch of a button, women’s safety, too, is something to be protected by willing women.

Sexual assault = Data problems

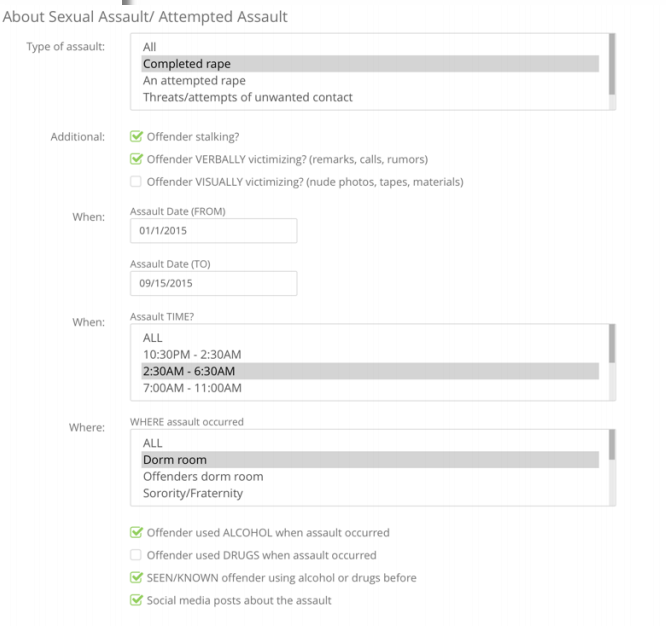

With personal safety gendered as women’s safety, campus sexual assault is framed as a data problem. Take Lighthouse as an example, an independent, web-based sexual assault reporting tool with encryption3.. Lighthouse enables users to document incidents of sexual assault, contact campus resource providers, and escalate their documentation as official reports to campus authorities. The platform encourages police reporting and prompts users to classify their experience into neat categories of assault to create predictive models to ‘improve outcomes on campus’ (see below).

Lighthouse homepage. Screengrab taken 3 August 2017

Lighthouse homepage. Screengrab taken 3 August 2017

Lighthouse displays a bias towards official reporting to campus authorities. When the user inputs information, the application creates an encrypted documentation of sexual assault; the user can then decide whether to escalate the disclosure form to a formal report by submitting it to campus authorities. Reporting in the higher education context however, involves multiple routes with varying degrees of anonymity, confidentiality, and answerability. A confidential disclosure to a counsellor, for example, may trigger different responses than, say, a disclosure to the campus security. However, Lighthouse does not clarify the difference between documentation, disclosure to counselling, reporting to campus Title IX coordinator Title IX is a component of Education Amendments of 1972 that requires education institutions receiving federal funding to proactively prevent and respond to gender-based discrimination that includes sexual violence and harassment. If a survivor chooses to report to the campus Title IX Coordinator, they may follow the school’s grievance procedures to obtain academic, residential, and extracurricular accommodations, enact no-contact orders, or put other safety measures in place. For details on Title IX reporting, see Know Your IX and Sokolow, and police reporting. They are all described as ‘reporting’.

‘Reporting Data’ from . Screengrab taken 4 August 2017.

‘Reporting Data’ from . Screengrab taken 4 August 2017.

How Lighthouse quantifies the user’s experience further reflects its focus on producing data, rather than supporting the user through the reporting process. One reason why victims do not report is their own perception of the legitimacy of their experience. Studies have shown that those who experienced what they perceived to be closer to ‘real rape’—involving physical coercion and injuries—are more likely to report to law enforcement. This means that there is a significant disconnect between legal classifications of sexual violence and survivors’ perceptions of their own experience (Herman, 1992). Sexual assault, according to Lighthouse, has ‘3 categories and 9 levels of assaults/harassment’ (see caption above). The user can ‘log a range of misconduct’ by clicking one of the pre-existing rape categories from a dropdown list. The platform not only presumes that the user is familiar with these classifications, but also prompts the user to label their experience as such.

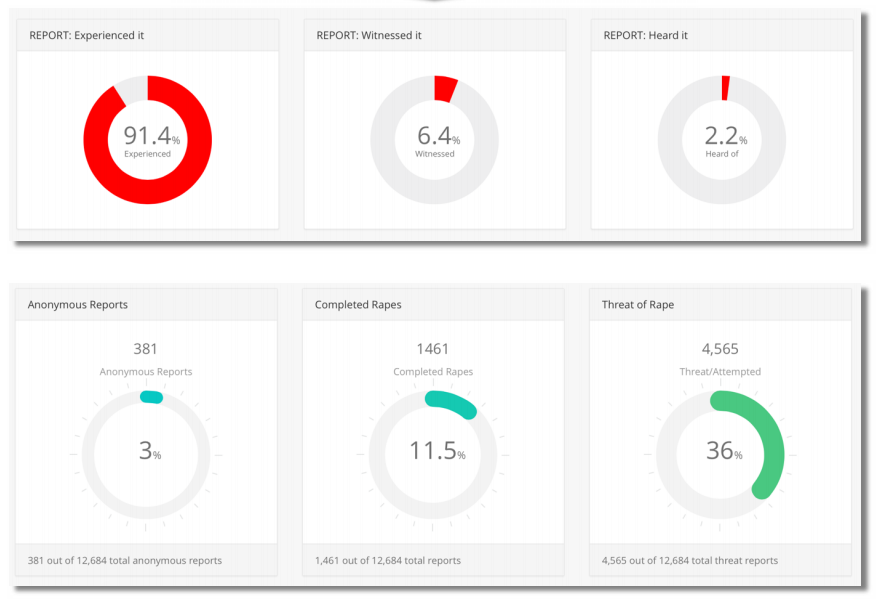

‘Real-time breakdown’ . Screengrab taken 4 August 2017.

‘Real-time breakdown’ . Screengrab taken 4 August 2017.

Lastly, Lighthouse claims to use de-identified, aggregate data to offer a ‘mapping of behaviour and trends on campus’, identify ‘frequency of external variables’, and detect ‘regional correlations’ to build a predictive model. The obvious privacy concern is that, regardless of de-identification, the platform is taking content-related data from users’ reports to visually represent information that could be de-anonymized. Moreover, this is done without explicitly obtaining the users' informed consent on how their sensitive and traumatic experiences could be used. This way of using ‘aggregate data’ is grounded in the assumption that more data adds up to better data and, thus, accurate predictions.

As Boyd and Crawford (2012) note in their text Critical Questions for Big Data: ‘Data are not generic. There is value to analysing data abstractions, yet retaining context remains critical, particularly for certain lines of inquiry’(p 671). This is especially true for data on sexual violence. Data on sexual assaults are often unrepresentative because collecting information relies on voluntary disclosure to campus authorities. By nature, existing data on sexual assault are always partial. In spite of this, what Lighthouse does in aggregating data into a predictive model is to ‘[see] patterns where none actually exist, simply because enormous quantities of data can offer connections that radiate in all directions’ (p 668).

Ultimately, how Lighthouse guides the user to quantify their experience and encourages police reporting is reflective of the wider cultural notion that sexual assault is a problem of accuracy where survivors’ experiences are meaningful, only if it can fit neatly into legal categories of assault.

Building an anti-rape technology

The desire for data is not inherently a misguided one, but when it is devoid of context, its perceived objectivity serves as yet another obstacle to survivors’ fight for credibility in a culture that regularly dismisses and blames them. This is not to denounce the potential for creative and purposeful technological contributions to combating gender-based violence. Callisto, a web-based platform for campus, gender-based violence documentation and reporting, serves as an exemplar of context-specific and participatory design processes. Callisto asks a series of trauma-informed questions to guide the user through recording their experience, and provides comprehensive information about on-campus reporting options. Its unique affordance is the matching feature, which reviews existing records to identify repeat offenders, which may incentivise the user to escalate their record to a report. The non-profit attributes these features to their model of campus partnership and extensive user research on, interviews with, and input from campus sexual violence survivors. By investigating the actual needs of survivors and focusing on the campus context, Callisto’s features meet their objective in supporting users through the complexity of campus reporting options. Callisto demonstrates what emerging technologies can do when they are embedded in actual contexts of use and invite input from users.

To build an anti-rape technology that actually meets a need, technologists, survivor advocates, and policymakers must critically engage with how technological solutionism and gendered assumptions about what sexual assault is (and isn’t) are mutually constitutive in the design process.

Endnotes

1The following accounts detail experiences of survivors who have faced dismissal, ignorance, and retaliation from their respective universities: Angie Epifano (2012) from Amherst College, Anna (2014) from Hobart and Smith College, Anonymous (2014) from Harvard University, Emma Sulkowicz (2014) from Columbia University, Wagatwe Wajunki (2014) from Tufts University.

For media coverage and further details on this topic, see: American Association of University Women, [End Rape on Campus](www.nwlc.org/issue/sexual-harassment-assault-in-schools/; Know Your IX, www.knowyourix.org/press-room/in-the-news/); [National Women’s Law Center](www./nwlc.org/issue/sexual-harassment-assault-in-schools/; and SurvJustice, www.survjustice.org/press.html).↩ 2Bucher, Taina, and Anne Helmond (2017). The Affordances of Social Media Platforms. Edited by J. Burgess, T. Poell, and A. Marwick. SAGE Handbook of Social Media. London. SAGE and Neff & Nagy (2015).↩ 3At the time this article was written, Lighthouse did not allow new accounts to be made, even though it is listed as live on its parent company Vertiglo Lab’s website. This may be in part due to controversial responses it received. According to a Huffington Post article, many critics objected to Lighthouse’s insistent on working independently from higher education to collect and make use of reporting data. Lighthouse may be on hold currently, but it has been included in this article as an example because of the widespread interest it spawned.↩

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Tactical Tech's editorial stance.

Kate is a PhD candidate at the Oxford Internet Institute researching the role of emerging technologies in shaping social and political understanding of gender, violence, and safety. Specifically, she focuses on the design and use of anti-rape technologies in the context of US higher education. She tweets @katejsim.

Protecting Students from Sexual Assault: Building Tools to Keep Students Safe and Informed

Lynn Rosenthal and Vivian Graubard

Rape: is there an app for that? An empirical analysis of the features of anti-rape apps

Rena Bivens & Amy Adele Hasinoff

Wearable Technology Contributing to the Sexual Assault Awareness Conversation

Karen Levy

The Role of “Real Rape” and “Real Victim” Stereotypes in the Police Reporting Practices of Sexually Assaulted Women

Janice Du Mont, Karen-Lee Miller & Terri L. Myhr

Sexual Assault Statistics Can Be Confusing, But They’re Not The Point

Tyler Kingkade

Meet Callisto, the Tinder-like platform that aims to fight sexual assault

Ian Ayres